در صورتی که اشکالی در ترجمه می بینید می توانید از طریق شماره زیر در واتساپ نظرات خود را برای ما بفرستید

09331464034Insight or evolution?

بینش یا تکامل؟

Two scientists consider the origins of <strong>discoveries</strong> and other innovative behavior.

دو دانشمند منشا <strong>اکتشافات</strong> و سایر رفتارهای مبتکرانه را بررسی می کنند.

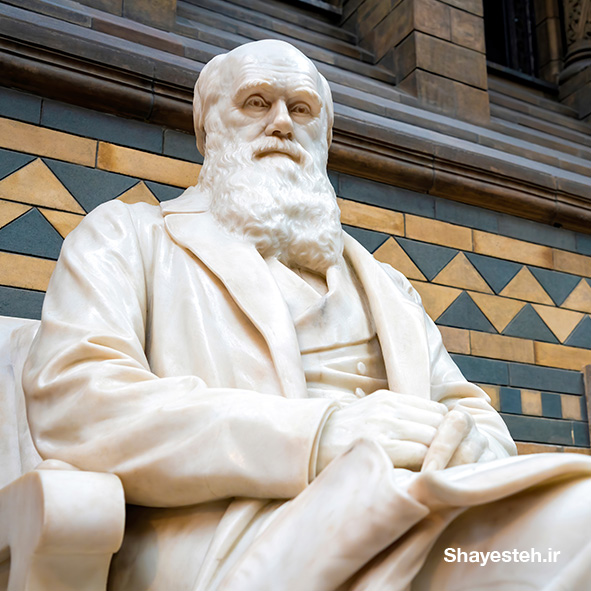

Scientific <strong>discovery</strong> is popularly believed to result from the sheer genius of such intellectual stars as naturalist Charles Darwin and theoretical physicist Albert Einstein.

اعتقاد عموم بر این است که <strong>اکتشافات</strong> علمی، ناشی از نبوغ محض نخبه های باهوش مانند چارلز داروین طبیعت شناس و آلبرت انیشتین فیزیکدان نظری است.

Our view of such unique contributions to science often disregards the person’s prior experience and the <strong>efforts</strong> of their lesser-known predecessors.

اما معمولا در دیدگاه ما در مورد چنین کمکهای منحصربهفردی به علم، تجربیات قبلی افراد و <strong>تلاشهای</strong> پیشینیانی که کمتر شناخته شده اند، نادیده گرفته می شود.

Conventional wisdom also places great weight on insight in <strong>promoting</strong> breakthrough scientific achievements, as if ideas spontaneously pop into someone’s head – fully formed and functional.

خرد متعارف همچنین سعم زیادی برای بینش در <strong>ارتقای</strong> دستاوردهای علمی مهم در نظر می گیرد، گویی ایدههایی- کاملاً شکل گرفته و کاربردی- به طور خود به خود به ذهن کسی خطور می کند.

There may be some limited <strong>truth</strong> to this view.

ممکن است در این دیدگاه تاحدودی <strong>حقیقت</strong> وجود داشته باشد.

However, we believe that it largely <strong>misrepresents</strong> the real nature of scientific discovery, as well as that of creativity and innovation in many other realms of human endeavor.

اما، ما معتقدیم که ماهیت واقعی اکتشافات علمی و همچنین خلاقیت و نوآوری در بسیاری از حوزههای دیگر تا حد زیادی تلاش انسان را <strong>نادرست نشان میدهد</strong>.

<strong>Setting</strong><strong> aside</strong> such greats as Darwin and Einstein – whose monumental contributions are duly celebrated – we suggest that innovation is more a process of trial and error, where two steps forward may sometimes come with one step back, as well as one or more steps to the right or left.

با <strong>کنار گذاشتن</strong> بزرگانی مانند داروین و انیشتین - که کمک های تاریخی آنها به درستی مورد تجلیل قرار می گیرد – ما معتقدیم که نوآوری بیشتر یک فرآیند آزمون و خطا است، جایی که ممکن است گاهی دو گام به جلو با یک گام به عقب و همچنین یک یا چند گام به سمت راست یا چپ همراه شود.

This <strong>evolutionary</strong> view of human innovation undermines the notion of creative genius and recognizes the cumulative nature of scientific progress.

این دیدگاه <strong>تکاملی</strong> نسبت به نوآوری انسان، مفهوم نبوغ خلاق را تضعیف می کند و ماهیت جمعی پیشرفت علمی را مشخص می کند.

Consider one unheralded scientist: John Nicholson, a mathematical physicist working in the 1910s who postulated the <strong>existence</strong> of ‘proto-elements’ in outer space.

یک دانشمند گمنام را در نظر بگیرید: جان نیکلسون، یک فیزیکدان ریاضی که در دهه 1910 کار می کرد و <strong>وجود</strong> «عناصر اولیه» را در فضای خارج از جو فرض کرد.

By combining different numbers of weights of these proto-elements’ atoms, Nicholson could <strong>recover</strong> the weights of all the elements in the then-known periodic table.

نیکلسون با ترکیب تعداد مختلف وزن اتمهای این عناصر اولیه، توانست وزن تمام عناصر جدول تناوبی که تا آن زمان شناخته شده بود را <strong>بازیابی</strong> کند.

These <strong>successes</strong> are all the more noteworthy given the fact that Nicholson was wrong about the presence of proto-elements: they do not actually exist.

با وجود این واقعیت که نیکلسون در مورد وجود عناصر اولیه اشتباه می کرد: آنها در واقع اصلا وجود ندارند، این <strong>موفقیت</strong> ها بیشتر قابل توجه است.

Yet, amid his often fanciful theories and wild speculations, Nicholson also proposed a novel theory about the <strong>structure</strong> of atoms. Niels Bohr, the Nobel prize-winning father of modern atomic theory, jumped off from this interesting idea to conceive his now-famous model of the atom.

با این حال، نیکلسون در میان تئوریهای اغلب خیالی و گمانهزنیهای دیوانه وارش، نظریه جدیدی درباره <strong>ساختار</strong> اتمها ارائه کرد. نیلز بور، پدر نظریه اتمی مدرن، برنده جایزه نوبل، از این ایده جالب شروع کرد تا مدل اتمی را که اکنون معروف شده است، بیابد.

What are we to make of this story? One might simply <strong>conclude</strong> that science is a collective and cumulative enterprise. That may be true, but there may be a deeper insight to be gleaned.

از این داستان چه می فهمیم؟ به سادگی می توان <strong>نتیجه گرفت</strong> که علم یک کار جمعی و تراکمی است. این ممکن است درست باشد، اما ممکن است بینش عمیق تری برای برداشت کردن وجود داشته باشد.

We propose that science is constantly evolving, much as <strong>species</strong> of animals do.

ما معتقدیم که علم دائماً در حال تکامل است، درست مانند <strong>گونه های</strong> حیوانات.

In biological systems, organisms may display new characteristics that <strong>result from</strong> random genetic mutations.

در سیستم های بیولوژیکی، موجودات ممکن است ویژگی های جدیدی را نشان دهند که از جهش های ژنتیکی تصادفی <strong>ناشی می شود</strong><strong>.</strong>

In the same way, random, arbitrary or accidental mutations of ideas may help pave the way for <strong>advances</strong> in science.

به همین ترتیب، جهشهای تصادفی، دلخواه یا رندوم ایدهها ممکن است به هموار کردن راه برای <strong>پیشرفت</strong> علم کمک کند.

If mutations prove beneficial, then the animal or the scientific theory will continue to thrive and perhaps <strong>reproduce</strong>.

اگر ثابت شود که این جهش ها سودمند هستند، آنگاه حیوان یا نظریه علمی به رشد خود ادامه خواهند داد و شاید <strong>تکثیر شوند</strong><strong>.</strong>

Support for this evolutionary view of behavioral innovation comes from many domains. Consider one example of an <strong>influential</strong> innovation in US horseracing.

از این دیدگاه تکاملی نسبت به نوآوری رفتاری توسط حوزههای زیادی پشتیبانی شده است. یک نمونه از یک نوآوری <strong>تأثیرگذار</strong> در مسابقات اسب دوانی ایالات متحده را در نظر بگیرید.

The so-called ‘acey-deucy’ stirrup placement, in which the rider’s foot in his left stirrup is placed as much as 25 centimeters lower than the right, is believed to confer important speed advantages when <strong>turning</strong> on oval tracks.

اعتقاد بر این است که قرارگیری پا در رکاب در حالتی که “اسی-دئوسی" نامیده می شود و در آن، پای سوارکار در رکاب سمت چپ تا 25 سانتیمتر پایینتر از رکاب سمت راست قرار میگیرد، در هنگام <strong>چرخش</strong> در مسیرهای بیضی شکل، در سرعت گرفتن او تاثیر قابل توجهی دارد.

It was developed by a <strong>relatively</strong> unknown jockey named Jackie Westrope.

این ایده، توسط یک سوارکار تازه کار <strong>نسبتا</strong> ناشناخته به نام جکی وستروپ ارائه شد.

Had Westrope conducted methodical investigations or examined extensive film records in a shrewd plan to outrun his rivals? Had he foreseen the speed advantage that would be conferred by <strong>riding</strong> acey-deucy? No.

آیا وستروپ تحقیقات علمی انجام داده بود یا سوابق تعداد زیادی فیلم را براساس یک نقشه زیرکانه به منظور پیشی گرفتن از رقبای خود بررسی کرده بود؟ آیا او مزیتی که در سرعت گرفتن با <strong>سواری</strong> به روش اسی-دئوسی به دست می آورد، پیش بینی کرده بود؟ خیر

He suffered a leg injury, which left him unable to fully bend his left knee. His modification just happened to coincide with enhanced left-hand turning <strong>performance</strong>.

او از ناحیه پا آسیب دید و نمی توانست زانوی چپ خود را به طور کامل خم کند. تغییرات او فقط با بهبود <strong>عملکرد</strong> چرخش در سمت چپ همزمان شد.

This led to the rapid and widespread adoption of riding acey-deucy by many riders, a racing style which continues in today’s thoroughbred <strong>racing</strong>.

این امر منجر به پذیرش سریع و گسترده سواری اسی دوسی توسط بسیاری از سوارکاران شد، سبک مسابقه ای که در <strong>مسابقات</strong> اصیل امروزی هنوز ادامه دارد.

Plenty of other stories show that fresh advances can arise from error, misadventure, and also pure serendipity – a happy accident. For example, in the early 1970s, two employees of the company 3M each had a problem: Spencer Silver had a product – a glue which was only slightly sticky – and no use for it, while his colleague Art Fry was trying to figure out how to affix <strong>temporary</strong> bookmarks in his hymn book without damaging its pages.

بسیاری از داستانهای دیگر نشان میدهند که پیشرفتهای تازه میتوانند از اشتباه، ماجراهای ناخوشایند و همچنین سعادت کامل ناشی از یک حادثه خوشحال کننده بوجود آیند. به عنوان مثال، در اوایل دهه 1970، دو کارمند شرکت 3M هر کدام یک مشکل داشتند: اسپنسر سیلور یک محصول داشت – چسبی که فقط کمی چسبناک بود – و هیچ کاربردی برای آن وجود نداشت، در حالی که همکارش آرت فرای تلاش می کرد بفهمد چگونه بوک مارک ها را به طور <strong>موقت</strong> در کتاب سرود خود بدون آسیب رساندن به صفحات آن اضافه کند.

The <strong>solution</strong> to both these problems was the invention of the brilliantly simple yet phenomenally successful Post-It note.

<strong>راه حل</strong> هر دوی این مشکلات اختراع برگه یادداشت فوق العاده ساده و در عین حال فوق العاده موفق Post-It بود.

Such examples give lie to the claim that ingenious, designing minds are responsible for human creativity and invention. Far more banal and mechanical forces may be at work; forces that are fundamentally <strong>connected to</strong> the laws of science.

چنین نمونه هایی این ادعا را دروغ می پندارند که ذهن های مبتکر و طراح، مسئول خلاقیت و اختراع انسان هستند. نیروهای بسیار پیش پا افتاده و مکانیکی ممکن است در کار باشند، نیروهایی که اساساً با قوانین علمی <strong>مرتبط هستند</strong><strong>.</strong>

The notions of insight, creativity and genius are often <strong>invoked</strong>, but they remain vague and of doubtful scientific utility, especially when one considers the diverse and enduring contributions of individuals such as Plato, Leonardo da Vinci, Shakespeare, Beethoven, Galileo, Newton, Kepler, Curie, Pasteur and Edison.

اغلب به مفاهیم بینش، خلاقیت و نبوغ <strong>استناد می شود،</strong> اما مبهم هستند و کاربرد علمی آنها با تردید همراه است، بهویژه زمانی که به سهم متنوع و پایدار افرادی مانند افلاطون، لئوناردو داوینچی، شکسپیر، بتهوون، گالیله، نیوتن، کپلر، کوری، پاستور و ادیسون توجه کنیم.

These notions merely label rather than explain the evolution of human innovations. We need another <strong>approach</strong>, and there is a promising candidate.

این مفاهیم به جای توضیح تکامل نوآوری های انسانی، صرفاً برچسب می زنند. ما به <strong>رویکرد</strong> دیگری نیاز داریم و یک گزینه امیدوار کننده وجود دارد.

The Law of Effect was advanced by psychologist Edward Thorndike in 1898, some 40 years after Charles Darwin <strong>published</strong> his groundbreaking work on biological evolution, On the Origin of Species.

قانون اثر توسط روانشناس ادوارد ثورندایک در سال 1898، حدود 40 سال پس از اینکه چارلز داروین نظریه پیشگامانه خود در زمینه تکامل بیولوژیکی مرتبط با منشاء گونه ها را <strong>منتشر کرد، </strong>ارائه شد.

This simple law holds that organisms <strong>tend</strong> to repeat successful behaviors and to refrain from performing unsuccessful ones.

این قانون ساده بر این باور است که ارگانیسم ها <strong>تمایل دارند</strong> رفتارهای موفق را تکرار کنند و از انجام رفتارهای ناموفق خودداری کنند.

Just like Darwin’s Law of Natural Selection, the Law of Effect involves an entirely mechanical process of variation and selection, without any end <strong>objective</strong> in sight.

درست مانند قانون انتخاب طبیعی داروین، قانون اثر شامل یک فرآیند کاملاً مکانیکی از تنوع و انتخاب است، بدون اینکه <strong>هدف</strong> نهایی در نظر باشد.

Of course, the origin of human innovation <strong>demands</strong> much further study.

البته، منشاء نوآوری بشر <strong>مستلزم</strong> مطالعه بیشتر است.

In particular, the provenance of the raw material on which the Law of Effect operates is not as clearly known as that of the genetic <strong>mutations</strong> on which the Law of Natural Selection operates.

به طور خاص، منشأ ماده خامی که قانون اثر بر اساس آن عمل میکند، به اندازه منشأ <strong>جهشهای</strong> ژنتیکی که قانون انتخاب طبیعی بر اساس آن عمل میکند، واضح و شناخته شده نیست.

The generation of novel ideas and behaviors may not be entirely random, but constrained by prior successes and failures – of the current individual (such as Bohr) or of predecessors (such as Nicholson).

تولید ایدهها و رفتارهای بدیع ممکن است کاملاً تصادفی نباشد، بلکه توسط موفقیتها و شکستهای قبلی یک شخص معاصر (مانند بور) یا پیشینیان (مانند نیکلسون) محدود شده باشد.

The time seems right for abandoning the naive notions of intelligent design and genius, and for scientifically exploring the true <strong>origins</strong> of creative behavior.

به نظر می رسد اکنون زمان مناسبی برای کنار گذاشتن مفاهیم ساده لوحانه طراحی هوشمندانه و نبوغ، و بررسی علمی <strong>ریشه های</strong> واقعی رفتار خلاقانه است.

Questions & answers

نظرات کاربران

هنوز نظری درج نشده است!