در صورتی که اشکالی در ترجمه می بینید می توانید از طریق شماره زیر در واتساپ نظرات خود را برای ما بفرستید

09331464034Jobs in ancient Egypt

مشاغل در مصر باستان

In order to be engaged in the higher <strong>professions</strong> in ancient Egypt, a person had co be literate and so first had to become a scribe.

برای اینکه شخصی در مصر باستان به <strong>مشاغل</strong> عالی مشغول شود، باید باسواد بوده و بنابراین ابتدا باید کاتب می شد.

The apprenticeship for this job lasted many years and was tough and <strong>challenging</strong>.

کارآموزی برای این شغل سال ها به طول می انجامید و سخت و <strong>چالش برانگیز</strong> بود.

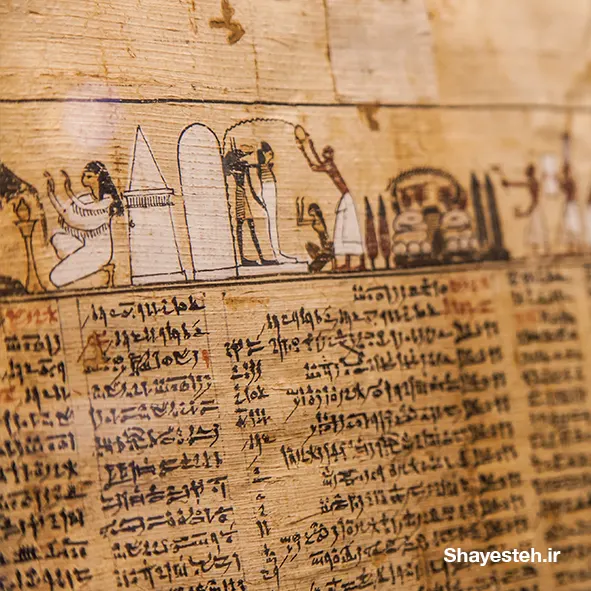

It principally involved <strong>memorizing</strong> hieroglyphic symbols and practicing handwritten lettering.

این چالش ها، اساساً شامل <strong>حفظ</strong> <strong>کردن</strong> نمادهای هیروگلیف و تمرین نوشتن حروف دست نویس بود.

Scribes noted the everyday activities in ancient Egypt and wrote about everything from grain stocks to tax <strong>records</strong>.

کاتبان به فعالیت های روزمره در مصر باستان اشاره می کردند و در مورد همه چیز از ذخایر غلات گرفته تا <strong>سوابق</strong> مالیاتی می نوشتند.

Therefore, most of our information on this rich <strong>culture</strong> comes from their records.

بنابراین، بیشتر اطلاعات ما در مورد این <strong>فرهنگ</strong> غنی از سوابق آنها می آید.

Most scribe s were men from <strong>privileged</strong> backgrounds.

بیشتر کاتبان مردانی با پیشینه های <strong>ممتاز</strong> بودند.

The occupation of scribe was among the most sought-after in <strong>ancient</strong> Egypt.

شغل کتابت یکی از پرطرفدارترین مشاغل مصر <strong>باستان</strong> بود.

Craftspeople endeavoured to get their sons into the school for scribes, but they were <strong>rarely</strong> successful.

پیشه وران تلاش می کردند تا پسران خود را به مدرسه کاتبان بیاورند، اما <strong>به ندرت</strong> موفق می شدند.

As in many civilizations, the lower classes <strong>provided</strong> the means for those above them to live comfortable lives.

مانند بسیاری از تمدن ها، طبقات فرودست وسایل زندگی راحت را برای افراد بالاتر از خود را <strong>فراهم می کردند.</strong>

You needed to work if you wanted to eat, but there was no <strong>shortage</strong> of jobs at any time in Egypt’s history.

اگر می خواستید غذا بخورید باید کار می کردید، اما در هیچ مقطعی از تاریخ مصر، <strong>کمبود</strong> شغل وجود نداشت.

The commonplace items taken for granted today, such as a <strong>brush</strong> or bowl, had to be made by hand;

اقلام معمولی که تولید آنها امروزه ساده در نظر گرفته می شود، مانند <strong>قلم مو </strong>یا کاسه، باید با دست ساخته می شدند.

laundry had to be washed by hand, clothing sewn, and sandals made from papyrus and <strong>palm</strong> leaves.

لباسهای شستنی باید با دست شسته میشد، لباسها دوخته میشدند و صندلها از پاپیروس و برگهای <strong>نخل</strong> ساخته میشدند.

In order to make these and have paper co write on, papyrus plants had to be harvested, processed, and <strong>distributed</strong> and all these jobs needed workers.

برای ساختن اینها و نوشتن روی کاغذ، گیاهان پاپیروس باید برداشت، فراوری و <strong>توزیع</strong> می شدند و همه این مشاغل به کارگران نیاز داشتند.

There were <strong>rewards</strong> and sometimes difficulties .

<strong>پاداش</strong> هایی وجو داشت و گاهی هم سختی هایی.

The reed cutter, for example, who harvested papyrus plants along the Nile, had to bear in mind that he worked in an area that was also home to wildlife that, at times, could prove <strong>fatal</strong>.

برای مثال، نیتراش که گیاهان پاپیروس را در امتداد رود نیل برداشت میکرد، باید در نظر داشت که در منطقهای کار میکرد که اقلیم حیات وحشی بود که گاهی اوقات میتوانست <strong>مرگبار</strong> باشد.

At the bottom rung of all these jobs were the people who served as the basis for the entire <strong>economy</strong>: the farmers.

در رده پایین همه این مشاغل، افرادی بودند که اساس کل <strong>اقتصاد</strong> بودند: کشاورزان.

<strong>Farmers</strong> usually did not own the land they worked.

<strong>کشاورزان</strong> معمولاً مالک زمینی که کار می کردند، نبودند.

They were given food, implements, and living quarters as <strong>payment</strong> for their labor.

به آنها غذا، وسایل و محل زندگی به عنوان <strong>مزد</strong> کارشان داده می شد.

Although there were many more glamorous jobs than farming, farmers were the <strong>backbone</strong> of the Egyptian economy and sustained everyone else.

اگرچه مشاغل پر زرق و برق بیشتر از کشاورزی وجود داشت، کشاورزان <strong>ستون فقرات</strong> اقتصاد مصر بودند و از بقیه حمایت می کردند.

The details of lower-class jobs are known from medical reports on the <strong>treatment</strong> of injuries, letters, and documents written on various professions, literary works, tomb inscriptions, and artistic representations.

جزئیات مشاغل طبقه پایین را از گزارش های پزشکی در مورد <strong>درمان</strong> جراحات، نامه ها و اسناد نوشته شده درباره مشاغل مختلف، آثار ادبی، کتیبه های مقبره ها و نمایش های هنری بدست آمده است.

This evidence presents a <strong>comprehensive</strong> view of daily work in ancient Egypt – how the jobs were done, and sometimes how people felt about the work.

این شواهد دیدگاهی <strong>جامع</strong> از کار روزانه در مصر باستان را ارائه میکند - اینکه چگونه کارها انجام میشد و گاهی اوقات مردم چه احساسی نسبت به آن کار داشتند.

In general, the Egyptians seem to have felt pride in their work <strong>no matter</strong> what their occupation.

به طور کلی، به نظر می رسد مصری ها نسبت به کار خود <strong>صرفنظر</strong> از شغلشان احساس غرور می کردند.

Everyone had something to contribute to the community, and no <strong>skills</strong> seem to have been considered non-essential.

هر کس، کاری برای کمک به جامعه داشت و به نظر می رسد هیچ <strong>مهارتی</strong> غیر ضروری تلقی نمی شد.

The potter who produced cups and bowls was as important to the community as the scribe, and the amulet-maker as vital as the <strong>pharmacist</strong>.

سفالگری که فنجان و کاسه تولید می کرد به اندازه کاتب برای جامعه اهمیت داشت و شغل اسلحه ساز به اندازه <strong>داروساز</strong> حیاتی بود.

Part of making a living, regardless of one’s <strong>special</strong> skills, was taking part in the king’s monumental building projects.

بخشی از امرار معاش، صرف نظر از مهارتهای <strong>خاص</strong> هر کس، مشارکت در پروژههای ساختمانی تاریخی پادشاه بود.

Although it is commonly believed that the great monuments and temples of Egypt were achieved through slave labor, there is absolutely no <strong>evidence</strong> to support chis.

اگرچه معمولاً اعتقاد بر این است که بناهای تاریخی و معابد بزرگ مصر از طریق کار بردگان به دست آمده اند، اما مطلقاً هیچ <strong>مدرکی</strong> برای حمایت از چنین چیزی وجود ندارد.

The pyramids and ocher monuments were built by Egyptian labourers who either donated their time as community service or were <strong>paid</strong> for their labor, and Egyptians from every occupation could be called on to do this.

اهرام و بناهای یادبود توسط کارگران مصری ساخته شده اند که یا وقت خود را صرف خدمات اجتماعی می کردند یا برای کار خود <strong>دستمزد</strong> دریافت می کردند و مصریان از هر شغلی می توانستند برای انجام این کار فراخوانده می شدند.

Stone had to first be quarried and chis required workers to <strong>split</strong> the blocks from the rock cliffs.

سنگ ابتدا باید به شکل مربع می شد و کارگران باید بلوک ها را از صخره های سنگی <strong>جدا می کردند.</strong>

It was done by <strong>inserting</strong> wooden wedges in the rock which would swell and cause the stone to break from the face.

این کار با <strong>فرو کردن </strong>گوههای چوبی در سنگ انجام میشد که متورم میشد و باعث میشد که سنگ از هر طرف آن بشکند.

The often huge blocks were then pushed onto sleds, devices better suited than wheeled vehicles to moving weighty objects over <strong>shifting</strong> sand.

سپس بلوکهای غالباً عظیم روی سورتمهها رانده میشدند، وسایلی که برای جابجایی اجسام سنگین روی شنهای <strong>متحرک</strong> مناسبتر از وسایل نقلیه چرخدار بودند.

They were then <strong>rolled</strong> to a different location where they could be cut and shaped.

سپس آنها را به مکان دیگری که بتوان برش داد و شکل داد، <strong>غلتانده</strong> می سدند.

This job was done by skilled stonemasons working with <strong>copper</strong> chisels and wooden mallets.

این کار توسط سنگ تراشان ماهر که با اسکنه های <strong>مسی</strong> و پتک های چوبی کار می کردند، انجام می شد.

As the chisels could gee blunt, a specialist in sharpening would take the tool, <strong>sharpen</strong> it, and bring it back.

از آنجایی که اسکنهها ممکن بود کند شوند، متخصص تیز کردن ابزار، آن را میگرفت، <strong>تیز میکرد</strong> و برمیگرداند.

This would have been <strong>constant</strong> daily work as the masons could wear down their tools on a single block.

این کار هر روز و <strong>ثابت</strong> بود زیرا سنگ تراشان مدام ابزارهای خود را روی یک بلوک می ساییدند.

The blocks were then moved into <strong>position</strong> by unskilled labourers. These people were mostly farmers who could do nothing with their land during the months when the Nile River overflowed its banks.

سپس بلوک ها توسط کارگران غیر ماهر به <strong>موقعیت</strong> خود منتقل می شدند. این افراد عمدتاً کشاورزانی بودند که در ماههایی که رودخانه نیل از کنارههای آن طغیان میکرد، نمیتوانستند روی زمین خود، کاری انجام دهند.

Egyptologists Bob Brier and Hoyt Hobbs explain: ‘For two months annually, workmen gathered by the tells of thousands from all over the country to <strong>transport</strong> the blocks a permanent crew had quarried during the rest of the year.

مصر شناسان، باب بریر و هویت هابز توضیح می دهند: «به مدت دو ماه در هر سال، کارگرانی حدود هزاران نفر از سراسر کشور جمع می شدند تا بلوک هایی را که یک گروه کارگر دائمی در بقیه ایام سال آن ها را استخراج کرده بودند، <strong>حمل کنند.</strong>

Overseers <strong>organized</strong> the men into teams to transport the stones on the sleds.’

ناظران، مردان را به صورت گروهی <strong>سازماندهی کردند</strong> تا سنگ ها را روی سورتمه حمل کنند.»

Once the pyramid was complete, the inner chambers needed to be decorated by scribes who painted elaborate images on the walls. Interior work on tombs and temples also required sculptors who could <strong>expertly</strong> cut away the stone around certain figures or scenes that had been painted.

هنگامی که هرم کامل شد، اتاقهای داخلی باید توسط کاتبانی تزئین میشد که تصاویر استادانهای روی دیوارها میکشیدند. کار داخلی بر روی مقبره ها و معابد همچنین به مجسمه سازانی نیاز داشت که بتوانند به طرز <strong>ماهرانه ای</strong> سنگ اطراف پیکره ها یا صحنه های خاصی را که نقاشی شده بودند، برش دهند.

While these artists were highly skilled, everyone – no matter what their job for the rest of the year – was <strong>expected</strong> to contribute co communal projects.

در حالی که این هنرمندان بسیار ماهر بودند، <strong>انتظار میرفت</strong> که همه - بدون توجه به شغلشان در بقیه سال - در پروژههای مشترک مشارکت داشته باشند.

This practice was in <strong>keeping with </strong>the value of ma’at (harmony and balance) which was central to Egyptian culture.

این عمل، با ارزش معات (هماهنگی و تعادل) که در فرهنگ مصری، یک اصل بود، <strong>مطابقت داشت.</strong>

One was expected to care for others as much as oneself and contributing to the common good was an <strong>expression</strong> of this.

از فرد انتظار می رفت که به اندازه خود به دیگران اهمیت دهد و کمک به نفع عموم، <strong>بیانگر</strong> این امر بود.

There is no doubt there were many people who did not love their job every day, bur the Egyptian government was aware of how hard the people worked and so staged a number of festivals throughout the year to show <strong>gratitude</strong> and give them days off to relax.

شکی نیست که افراد زیادی بودند که هر روز عاشق کار خود نبودند، اما دولت مصر از سخت کوشی مردم آگاه بود و به همین دلیل در طول سال جشنواره های متعددی را برای نشان دادن <strong>قدردانی</strong> و دادن روزهای مرخصی به آنها برگزار کرد.

Questions & answers

Questions 28-32

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

Write the correct letter in boxes 28-32 on your answer sheet.

- What does the writer say about scribes in ancient Egypt?

A. Their working days were very long.

B. The topics they wrote about were very varied.

C. Many of them were once ordinary working people.

D. Few of them rfs11j.&gd, the true value of their occupation.

- What is the writer doing in the second paragraph?

A. explaining why jobs were plentiful in ancient Egypt

B. pointing out how honest workers were in ancient Egypt

C. comparing manual and professional work in ancient Egypt

D. noting the range of duties an individual worker had in ancient Egypt

- What is the writer doing in the fifth paragraph?

A. explaining a problem

B. describing a change

C. rejecting a popular view

D. criticising a past activity

- The writer refers to the value of ma'at in order to explain

A. how the work of artists reflected beliefs in ancient Egypt.

B. how ancient Egyptians viewed their role in society.

C. why the opinions of certain people were valued in ancient Egypt.

D. why ancient Egyptians expressed their views so readily.

- Which word best describes the attitude of the Egyptian government toward its workers?

A. strict

B. patient

C. negligent

D. appreciative

Questions 33-36

Look at the following statements (Questions 33-36) and the list of jobs below. Match each statement with the correct job, A-G.

Write the correct letter, A-G, in boxes 33-36 on your answer sheet

- was unable to work at certain times

- divided workers into groups

- faced daily hazards

- underwent a long period of training

List of Jobs

A. scribe

B. reed cutter

C. farmer

D. potter

E. stonemason

F. overseer

G. sculptor

Questions 37-40

Complete the summary below.

Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the text for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 37-40 on your answer sheet.

The king's building projects

Labourers who worked on the king's buildings were local people who chose to participate in 37 _______or who received payment.

The work involved breaking up stone cliffs using wooden wedges. The large pieces of stone were then transported to another site on sleds, which moved easily over the 38 _______ Here, the blocks could be cut and shaped using tools made of 39 __________ and wood. Some of these had to be sharpened regularly.

Eventually, the stone was moved into place to create a building. The job of moving the Stone was often done by 40 __________ or other unskilled workers.

نظرات کاربران

هنوز نظری درج نشده است!